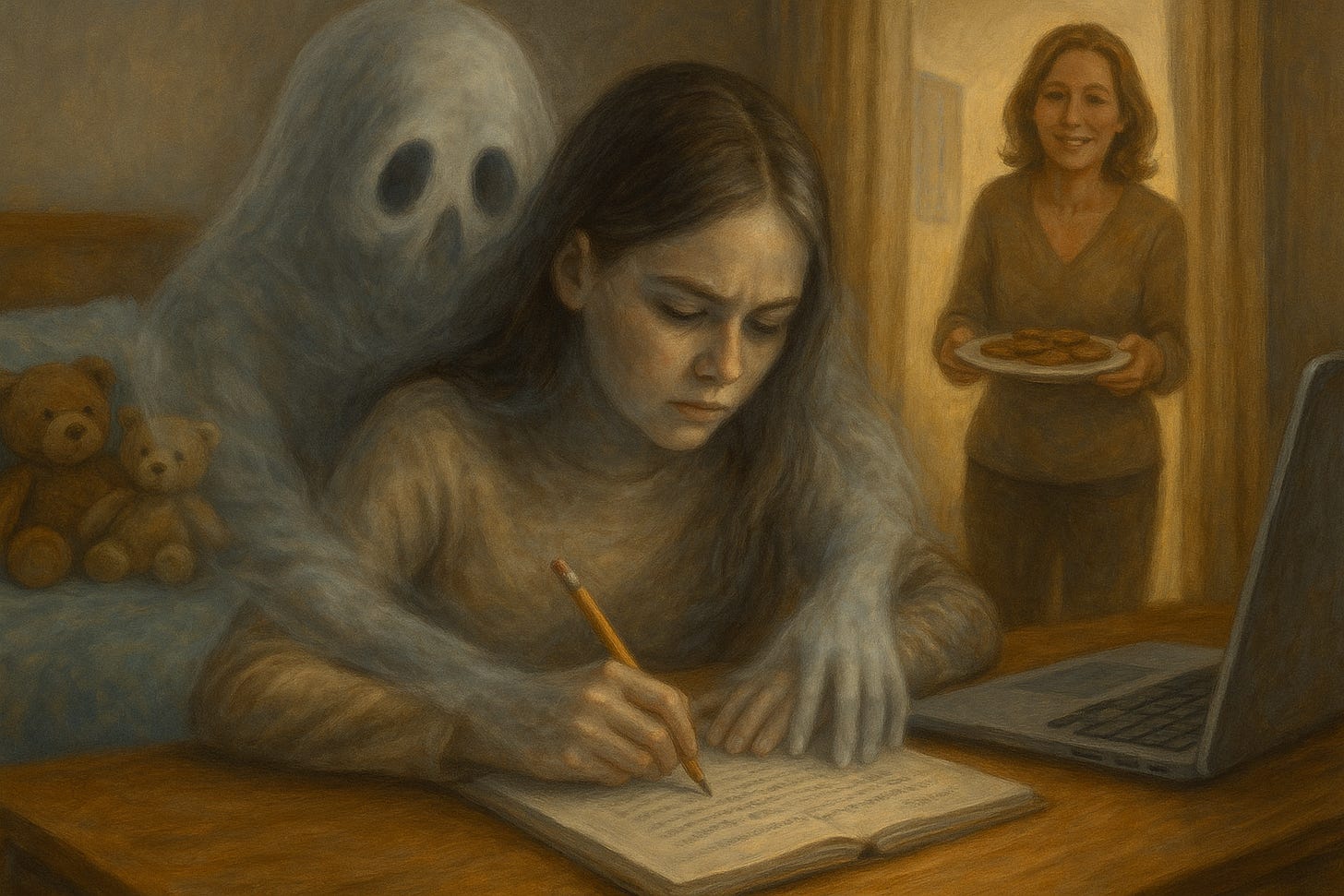

The Ghost in the Machine

BACK-TO-SCHOOL ESSAY: How AI is killing take-home assignments and forcing education to rely on labs and tests

As a student, I found a sort of comfort in the quiet, deliberate work of an assignment. There was something reassuring about taking time to refine thoughts and handing in a thing that was my own. Tests were another matter — annoying and stressful. Eventually, and this may surprise some readers, I earned a master’s degree in computer science, with a spe…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ask Questions Later to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.