Despite the dumbing down, books will survive

While music has moved to a hell of streaming bits and bytes, books sales are at record highs. One reason is that they make such fine decoration.

Here’s a picture worth 1,000 words: the bookstore at Ben Gurion Airport bravely marches on, with its week-old copies of the Economist and disorderly piles of bestsellers; to the right, the former music shop offers cables, headsets and electronic paraphernalia amid a nearly extinct selection of CDs. There seems to be a story there.

Yup — CDs are toast. That appears to condemn the music experience to a streaming hell of bits and bytes (unless you belong to the retro youth squad unaccountably attracted to vinyl LPs) — whereas I’m here to declare that books will certainly survive.

Indeed book sales are at record highs: according to recent reports almost 789 million specimens were sold in the United States last year, the second-highest figure this century (after pandemic-addled 2021) and a full third higher than a decade earlier.

Why is this, when books are just a digitizable as music? When Big Tech would like nothing more than to kill them off as well, in a mad rush to a metaverse-based future where fiction is produced by Bard and consumed by ChatGPT?

It is appealing to think it’s because the masses so love the written word that they insist on the tactile experience of grasping its physical manifestation. Of leafing through the pages, smelling the ink and highlighting passages the better to revisit their wit, insight, and brilliance.

But I do not think so. Most people never did and will not in the future read all that much. These days, people think reading is looking at a text. A single page will get them rolling their eyes and saying something like “TMI.”

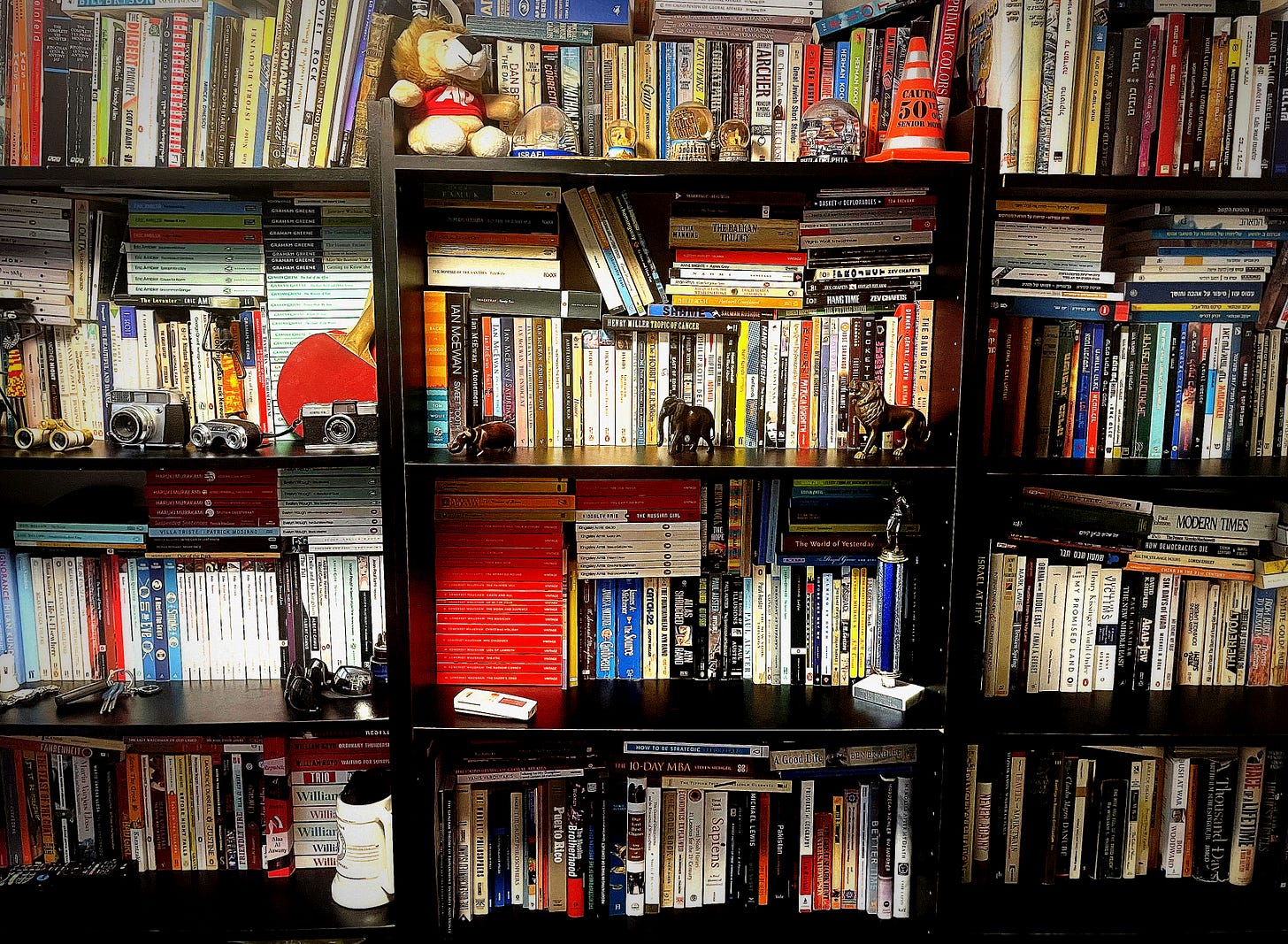

No, books will survive because a minority of the people will not only read them once but like to then flaunt them as furniture and decoration in their homes. I am not ashamed to say I do this as well. My home office boasts close to 1,000 books, arranged various ways, like yellowing trophies, most of which I have read just once.

My Londonian friend James owns multiple times more, and shows them off without the slightest shame; like me, he clearly hopes it will lend him a literate air. I’ve never had the heart to advise him that the effect is undone when he then, without irony, also refers to the ledger of his investments as “my book.” Finance people actually do this.

Anyway, if a person is so inclined — and I sometimes am, as certainly is James — there are many worse things to do than spending long hours immersed in such works.

I recently have read almost everything by Guy de Maupassant, a libertine Frenchmen of the 19th century who writes about rascals from what seems like personal knowledge. He lends naughtiness the gravitas of intellectual pursuit.

My shelves groan with collections of Nabokov and Kundera, the Bronte sisters, Zweig and Waugh, Maugham and Kingsley Amis (not the more pedestrian son). There is little there that is American, I am sad to say (except for Kurt Vonnegut, Edith Wharton, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Damon Runyon) or current (except for Egyptian Alaa Aswany and the valiant Brits Ian McEwan and William Boyd; long may they scribble).

There is a distinct preference for fiction, which I find contains more fundamental truth than non-fiction, limited as the latter is to the little that the writer has actually seen, heard or learned. When one is tired of fiction, one is tired of life. It makes me sad to hear busy executives (or lying politicians) say they only read biographies.

I sometimes just look at these shelves and derive pleasure and pride. These are not not sensations that Kindle can readily provide.

Which brings us to the sad fate that has befallen the various media that carried music. Only a handful of fanatics buy them anymore. I am a music lover, but stopped buying CDs myself a few years ago. For a while I held out with iTunes, which at least gave one the absurd satisfaction of “owning” the electrons. But it’s now all Spotify for me.

This is clearly a terrible shame. There is no comparing a streaming playlist to the physical object that comes with artwork and lyrics and a booklet perhaps illustrated by the artist, or the artist’s graphic artist.

The people of the world need objects to avoid feeling like some version of subjects. We need the rush of owning things. Why, then, have we abandoned musical things?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ask Questions Later to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.