Unbrexit?

ALISON MUTLER WRITES: In Munich, Starmer stressed that “we are not the Britain of the Brexit years anymore”

By Alison Mutler

Something potentially consequential emerged from the Munich Security Conference: The chill wind coming in from the United States is pushing the European Union and the Britain a little bit closer to coming together again.

Consider a simple fact: Europe accounts for 20 percent of America’s exports – not bad, offering leverage if Americans would wake up to it. Add the UK and the figure at over a quarter, representing approximately $700 billion. That is more leverage. The two combined also account for the vast majority of foreign direct investment in the US – millions of jobs might focus Americans’ minds on the stupidity of a rupture.

For years, Brexit politics rested on an implicit promise: that the United Kingdom, liberated from Brussels, would rediscover global agility. “Global Britain” would flourish, striking bespoke trade arrangements, reclaiming regulatory sovereignty, and leaning confidently into the Anglosphere — above all, the United States. The European Union might be geographically close, but the future, voters were told, was global.

To support the defense of discourse, decency and reason, consider unlocking full access to Ask Questions Later by upgrading to a Paid Subscription

Reality has been less accommodating. The notion that the United States — particularly under a figure like Donald Trump — would embrace Britain in some privileged economic partnership has steadily dissolved. Trade negotiations proved stubbornly difficult, repeatedly stalling over familiar disputes: agricultural standards, food safety rules, pharmaceutical pricing, and digital regulation. American negotiators pressed for expanded access for US farm products, while British officials resisted changes that could undermine domestic regulations or complicate relations with Europe.

Finally, in mid-2025, Washington and London announced the Economic Prosperity Deal, presented as a breakthrough in post-Brexit trade relations. Yet its structure revealed the limits of that achievement. Tariff reductions were targeted, quota-based, and largely implemented through executive authority rather than durable treaty law. Preferences could be revised or withdrawn with comparatively little institutional constraint. Market access depended less on fixed rules than on political judgment. For Britain, the implication was that unlike in the EU’s system of treaty-anchored commitments, the US–UK arrangement left important trade benefits exposed heavily to presidential discretion, meaning the whims of Trump.

More broadly, British officials confronted the fact that the United States, regardless of administration, does not view the UK as an economic priority warranting exceptional treatment. The rhetoric of a transformative Anglo-American partnership never produced the sweeping agreement once promised. Washington engages Britain warmly, certainly, but not preferentially. America’s strategic focus remains overwhelmingly continental and Pacific.

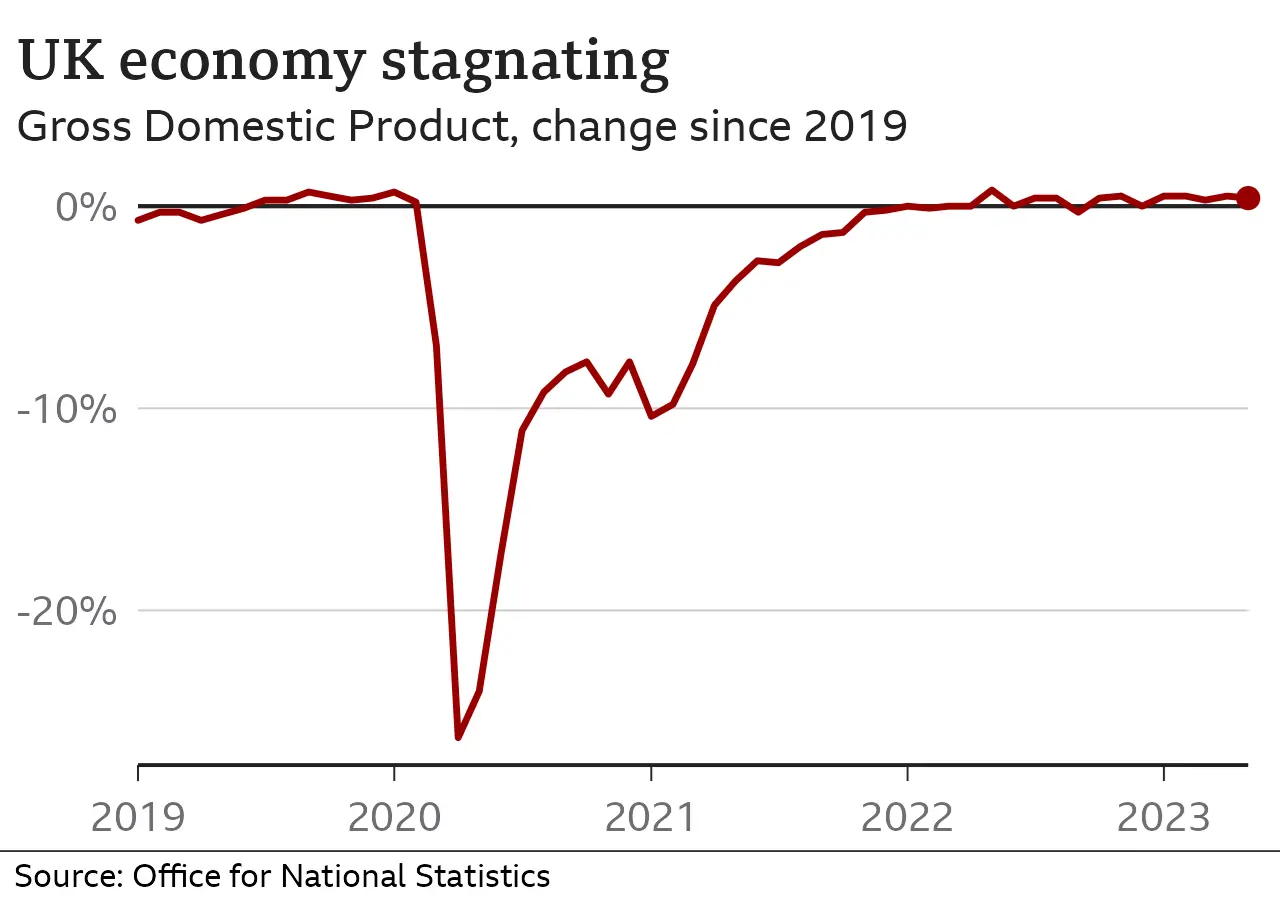

Meanwhile, trade talks with other potential partners have also proven difficult, leaving Britain mired in a condition of economic stagnation. Growth has been persistently weak, productivity gains subdued, and investment levels slow to recover their pre-Brexit trajectory. Global conditions and post-pandemic disruptions have contributed, but prolonged uncertainty over trade arrangements and regulatory alignment has weighed heavily on business confidence. Exports face new frictions, while the hoped-for surge in trade-driven dynamism has largely failed to offset reduced integration with the European Union. The picture is not collapse but drift — an economy growing, yet too slowly to deliver the renaissance once promised.

Immigration, the anger at which caused much of the Brexit vote, has meanwhile gone up, not down.

Brexit’s economic rationale always depended on credible alternatives to the EU’s single market. Without them, geography exerts its old, stubborn gravity. The EU remains Britain’s dominant trading partner, regulatory neighbor, and unavoidable economic ecosystem. Each year outside that framework compounds frictions that no quantity of patriotic resolve can dissolve.

The Labour government led by Keir Starmer plainly understands this dilemma, even if it speaks cautiously.

In Munich, Starmer made several statements and policy signals indicating a shift toward closer cooperation with the EU and European partners, a departure from the strained post-Brexit years. Starmer stressed that “we are not the Britain of the Brexit years anymore,” signaling a break with the isolationist rhetoric that followed the UK’s EU departure and emphasizing shared security interests with the continent.

Starmer (full speech below) called for stronger European defense collaboration, arguing that Europe must stand on its own two feet and reduce over-dependence on the United States while maintaining NATO ties — and suggested deeper links between the UK and EU across defense, industry, technology, and the wider economy. He also highlighted the potential for closer economic alignment with the EU single market in areas of mutual benefit.

Together, these statements at Munich reflect a strategic pivot that moves the UK away from the post-Brexit stand-alone posture and toward greater integration with European security and economic frameworks, even without formal EU membership. This represents an important political signal about the direction of UK–Europe relations in 2026.

This comes a week after Chancellor Rachel Reeves (the finance minister) argued that Labour’s recent agreements with the European Union represented only “first base,” describing closer ties with Brussels as the “biggest prize” for strengthening Britain’s sluggish economy and long-term security. Reeves invoked what she called the “reality of economic gravity,” noting that nearly half of UK trade remains tied to the EU and that Britain trades almost as much with Europe as with the rest of the world combined.

Framing Europe as one of the world’s three decisive economic blocs alongside the United States and China, she emphasized the strategic logic of reinforcing continental ties rather than deepening separation. Critics, particularly within the Conservative Party, seized on the remarks as evidence of an effort to dilute Brexit, while Reeves cast the position as pragmatic economics rather than ideological revisionism.

Taken together, these signals suggest a strategic pivot away from post-Brexit detachment toward greater European integration, even without formal EU membership. They represent an important political indicator of the direction of UK–Europe relations.

Labour’s constraint, however, is domestic. The party governs with a commanding parliamentary majority yet suffers persistent unpopularity. That is a paradox produced by Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system. In 2024 Labour converted just over a third of the vote into a landslide because its opposition fragmented. That structural advantage now looks less like triumph than temporary reprieve — because Labour’s side is now fragmenting as well.

Reform UK, energized by Nigel Farage, looms large. The Conservatives remain wounded but viable. The Liberal Democrats persist. The Greens have matured into a meaningful force. Britain increasingly resembles Europe’s multi-party landscape — but without Europe’s proportional mechanisms to stabilize it. Labour risks being wiped out. Or the results could look quite random.

In such conditions, managing drift rarely secures political survival. Governing parties require galvanizing projects capable of reshaping loyalties. Brexit’s unresolved contradictions may offer Labour precisely such an opportunity.

Public sentiment has shifted markedly since 2016. Regret over Brexit is now widespread, at perhaps 60 percent, yet the country recoils from reopening the emotional carnage of those years. This is Britain’s peculiar stalemate: dissatisfaction without mobilization. Politicians tread carefully because Brexit remains culturally radioactive even as its economic consequences harden.

But political incentives evolve. Labour has already lost much of the socially conservative Brexit vote to Reform. Chasing those voters risks futility. Its more reliable constituencies — urban, younger, professional, internationally oriented — are overwhelmingly pro-European. Re-energizing them carries its own logic.

Munich indirectly underscored why. The United States offers no compensatory anchor. American administrations prioritize scale and leverage; the EU provides both. Britain alone does not. Without a transformative US windfall, sustained distance from Europe weakens on pragmatic grounds.

This is less a story of ideology than arithmetic.

A Labour leadership facing bleak electoral prospects may eventually conclude that closer EU alignment — framed as repair rather than reversal — represents adaptation to post-Brexit reality. Incremental steps, such as customs union arrangements or sector-specific regulatory cooperation, could be presented as measures to reduce barriers, restore growth, and stabilize investment flows.

Such a shift could also reorder political dynamics, potentially enabling cooperation with other pro-European parties and reshaping electoral competition. The risks would be considerable. Brussels would demand acceptance of rules accumulated in Britain’s absence, financial obligations, and political discipline. Trust would not be automatic.

Yet Europe’s incentives are hardly trivial. British reintegration would strengthen the Union economically and geopolitically at a moment of profound strategic uncertainty. Munich highlighted that broader context: European security architecture is being recalibrated amid Russian aggression and fluctuating American engagement. Britain remains militarily and diplomatically significant; institutional estrangement complicates coordination strategic necessity increasingly demands.

None of this implies imminent re-entry into the European Union. The more plausible path would be incremental, technocratic, and framed in pragmatic language: stability, growth, competitiveness, security. But eventually, perhaps. Politics, sooner or later, as Reeves herself said, will crash down to earth.

Alison Mutler is a veteran British journalist who has worked with the Associated Press and is currently the director of Universul.net in Bucharest